Hello, and greetings from the Central Office! It has been an exciting summer of travel. I had the opportunity to speak at HOPE and bSides Las Vegas, and was able to connect with hackers from all over the world. It’s always really exciting to meet and talk with really smart people, and based on the conversations I had this summer, I’m convinced that we’re really on the cusp of a technological revolution with one of the greatest convergences of computing and telecommunications the world has ever seen. The future is only going to get more exciting.

If you asked me in 1999 what I thought would be the most game-changing innovation in telecommunications, I would have said VoIP. There was a lot of really exciting stuff happening then, and the VoIP scene did in fact explode over the next few years. Broadband was beginning to become widely available, with speeds of 1.5Mbps or more at affordable prices. The release of the first version of Asterisk brought the exciting possibility of running virtual telephone switchboards completely untethered from the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN), and shortly thereafter, Jeff Pulver’s FreeWorldDialup exploded onto the scene with a free, open, and public directory service that anyone could use to reach VoIP services all over the world. Amazingly, the FCC ruled—in a clear nod to encouraging technological development–that FreeWorldDialup was to be considered a “digital information service” and wasn’t subject to any of the regulations encumbering the PSTN. Creating a free, public directory resulted in all sorts of VoIP services being able to reach one another at no cost through virtual “tie lines” without ever touching the public switched telephone network (and generating no long distance charges).

Closer to home for hackers, in an unprecedented crossover of the phreak and hacker worlds, the Telephreak group melded computers with phones and released a full-fledged, grassroots, information and conferencing service that was accessible both via telephone and the Internet. Meanwhile, practically every instant messaging service from MSN Messenger to Skype to the (then-new) Google Chat added voice chat capability. It seemed that VoIP was an unstoppable force. The only thing missing, surprisingly, was the users. Despite technological advances and wide availability, VoIP remained the geeky domain of VoIP hackers, IT workers, and international students keeping in touch with their families and friends at home.

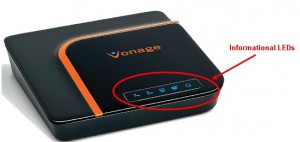

This is because as quickly as the explosion of broadband made VoIP possible, the world had changed even more quickly. The explosion in mobile phones made our society much more on-the-go, and calling people on the telephone from a fixed location was just too cumbersome. We began communicating in shorter bursts, and SMS became a more popular way than voice to communicate. While voice communications didn’t go away, the nascent VoIP provider market suffered from infighting. Vonage delinked its services from public directories, other VoIP providers suffered from consolidation, lack of differentiation and sometimes bankruptcy, and the market fragmented into retail and wholesale. The PSTN—with all of its attendant regulatory costs and regulatory headaches—maintained its status as directory provider for voice communications. Consumer VoIP services, software-driven, largely migrated onto hardware devices like magicJack, Vonage and Ooma. Skype was a glaring exception, having gained a foothold on university campuses worldwide and gaining popularity as a platform for video chat. On the consumer side of the business, it was simply easier to package and sell VoIP services if they were bundled with a relatively foolproof hardware product.

Meanwhile, in Central Offices everywhere, circuit-switched telecommunications gear began to be replaced by VoIP. The first big VoIP switch came with mobile phone carriers, which could easily transition long-distance service to VoIP trunks. Later, mobile phone carriers began exchanging traffic directly with one another via VoIP, as they exchanged SMS messages with one another over the Internet. Long distance carriers weren’t far behind, transitioning almost the entirety of their backbones from circuit-switched to VoIP trunks. To maintain quality of service, most “carrier-grade” long distance networks don’t use the Internet to transport calls, even though they use VoIP technologies. Instead, carriers operate their own private IP networks, separate and distinct from the Internet. Nonetheless, the cost of operating VoIP networks is much lower than operating circuit-switched networks, the capacity is greater, and—although it pains me to say it—reliability and cost of maintenance are both better. Late nights hunting down scratchy channels on recalcitrant DS-3s are, these days, a thing of the past.

While traditional POTS land line phones are still circuit-switched, connecting through the same 5ESS and DMS100 offices they did 20 years ago, land lines are largely migrating to VoIP as well. Based on the port-out rate at my Central Office, I would estimate the ratio of landlines is now nearly 50% VoIP. Although Vonage, magicJack and Ooma (among other services) have operated consumer VoIP service for years, even AT&T has gotten into the game with their uVerse product. Cable companies have, for years, offered landline replacement services (operating as CLECs), and these are all VoIP based. Eventually land lines are going to have to be all-VoIP; a 5ESS is practically an antique these days and has less computing power in sum total than my smartphone. It’s getting harder and harder to find replacement parts, and old-timers who still know how to maintain them are retiring at an alarming rate.

This giant piece of switching equipment, filling much of a building, has less computing power than my smartphone.

These days, with the growth of mobile phones, I see an opportunity for another wave of consolidation with VoIP. In order to use a SIP account, a MagicJack, and mobile phone service, I used to need three different devices. However, my $200 unlocked Android smartphone (a Moto G) now comes with four 1.4GHz processor cores, 16GB of solid state storage, and almost 1GB of RAM. When you consider that these specs roughly equal those of a well-equipped PC as little as 5 years ago (and actually exceed those of then-popular netbooks), it’s pretty eye-opening. So much can now be done in software.

Instead of using the magicJack hardware device, I can use their Android app. This is really handy in my new apartment, where mobile phone coverage is poor. Google Voice has its own smartphone app, which makes it practical for me to change my phone number once a month in order to take advantage of “new customer” deals with prepaid mobile phone providers (this is easily possible with an unlocked phone). My mobile phone service now costs me as little as $5 per month. And finally, I can enjoy wholesale rates on long distance calls through a SIP provider. Using the cSIPSimple app, I was able to migrate over the configuration from my SIP ATA, another hardware device. So, three different hardware devices have now consolidated into a single device that both costs less and does more than any one of the single individual devices I had before.

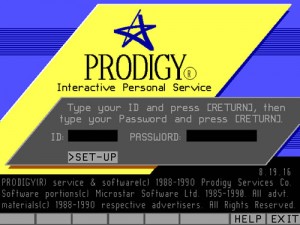

I think that smartphone apps are really the next wave in consumer VoIP and could actually have the Trojan horse potential to become the most disruptive threat the world of telecommunications has ever seen. After all, there isn’t any particular reason why you should need to have a telephone number anymore. They’re long, complicated, and hard to remember. However, in order for this to work, a free, universal and open directory service—which could entirely replace the PSTN—would need to be developed. This would be more or less along the lines of what Jeff Pulver originally envisioned with FreeWorldDialup. However, the market is Balkanized right now, with practically everyone playing in the space—from Google to Microsoft to Facebook—trying to own a “walled garden.” Everything old is new again, and the parallels to Prodigy, CompuServe and AOL two decades ago are astounding. Could the utility of a free and open network with a universal directory service supplant the tired, old model of telephone numbers, as the Internet did CompuServe? With the advent of IPv6 and the possibility of virtually unlimited Internet top level domains, I think that this is—for the first time—a real possibility. The only thing missing is the right software.

Hackers are, as always, true visionaries who drive technology forward, and I think the reason why we often succeed where others fail is that we care about technology for its own sake. Jeff Pulver’s original vision for FreeWorldDialup ultimately failed when the nascent VoIP scene failed to maintain unity (and it really didn’t help that Jeff tried to turn FreeWorldDialup into a business, which ultimately failed). The opportunity is still there, though. Imagine a world where telephone numbers weren’t necessary, and long distance charges—which, honestly, are an absurd concept in the year 2014—were utterly abolished. The only things standing in the way of this vision are essentially every government in the world (for whom surveillance would become more difficult) and the entrenched interests of the telecommunications industry. Yeah, that. Most people would be too intimidated. Hackers and phreaks have never been afraid to speak truth to power, though, and have never been afraid to challenge the status quo. That’s why I’m confident that change is coming. It’ll be exciting to see what app hackers produce in the next few years.

And with that, it’s time for me to run to a meeting. I can’t really talk about what my employer is planning, but nothing good will come of it. Or maybe it ultimately won’t matter. The path forward is really up to you.